Tuesday, October 31, 2017

Avoid the Rich

Greek Anthology 10.61 (by Palladas; tr. W.R. Paton):

For the sentiment, see also Aristophanes, Wealth 563-564 (Poverty speaking; tr. Jeffrey Henderson):

Art Young, Capitalism

Avoid the rich; they are shameless, domestic tyrants,The same, tr. Tony Harrison:

hating poverty, the mother of temperance.

Φεύγετε τοὺς πλουτοῦντας, ἀναιδέας, οἰκοτυράννους,

μισοῦντας πενίην μητέρα σωφροσύνας.

Shun the rich, they're shameless sodsThis is the only example of οἰκοτύραννος in Liddell-Scott-Jones.

strutting about like little gods,

loathing poverty, the soul

of temperance and self-control.

For the sentiment, see also Aristophanes, Wealth 563-564 (Poverty speaking; tr. Jeffrey Henderson):

Turning now to the issue of morality, I'll proceed to demonstrate

that good behavior dwells with me, and arrogance with Wealth.

περὶ σωφροσύνης ἤδη τοίνυν περανῶ σφῷν κἀναδιδάξω

ὅτι κοσμιότης οἰκεῖ μετ᾿ ἐμοῦ, τοῦ Πλούτου δ᾿ ἐστ᾿ ἐνυβρίζειν.

Home Security: Perimeter Defense

G.K. Chesterton, Illustrated London News (September 26, 1925):

I for one should love to have a real moat round my house, with a little drawbridge which could be let down when I really like the look of the visitor. I do not think I am a misanthrope. I am only an Englishman — that is, an islander — and one so very insular that he would like even his house to be an island.

Party Politics

The Life of George Crabbe By His Son (London: Oxford University Press, 1932), p. 168:

But of this I am sure, that his own passions were never violently enlisted in any political cause whatever; and that to purely party questions he was, first and last, almost indifferent.Id., p. 169 (quoting from a letter of J.W. Croker):

[H]e seemed to me to think and care less about party politics than any man of his condition in life that I ever met.Id., p. 170:

He says, in a letter on this subject, 'With respect to the parties themselves, Whig and Tory, I can but think, two dispassionate, sensible men, who have seen, read, and observed, will approximate in their sentiments more and more; and if they confer together, and argue, — not to convince each other, but for pure information, and with a simple desire for the truth, — the ultimate difference will be small indeed....'

Critical Apparatus

Tom Keeline, "The Apparatus Criticus in the Digital Age," Classical Journal 112.3 (2017) 342–363 (at 342):

It is a truth universally acknowledged that no one except textual critics and pedants actually reads an apparatus criticus. Why should they? Consider how few "general readers" read footnotes. Now picture those footnotes festooned with cryptic symbols, cloaked in the obscurity of a learned language, and provided without any superscript signaling in the main text that there might be something relevant at the bottom of the page—then add in the pervasive notion that the apparatus is merely a repository for what the editor thinks does not belong in the text.Id. (at 349-350, footnote omitted):

In my experience, undergraduates and graduate students rarely look at the "crapparatus," as I once heard it disparagingly called, unless a commentary or a professor draws attention to a particular point.Related post: Kitchen-Refuse?

Monday, October 30, 2017

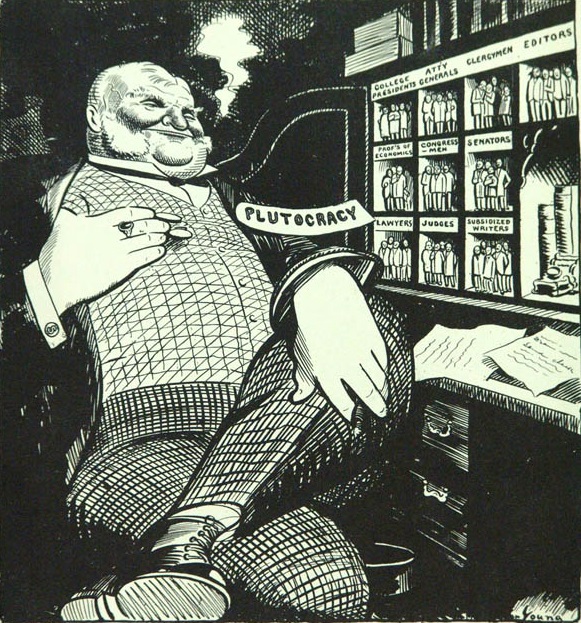

Plutocracy and Piracy

G.K. Chesterton, Illustrated London News (January 7, 1928):

Art Young, Plutocracy

Certainly, if I have to choose between plutocracy and piracy, I prefer the pirates; for that sort of crime necessitated some sorts of virtue. The pirate who grew rich on the high seas at least could not be a coward; the pirate who grows rich on the high prices may be that, as well as everything else that is unworthy. Besides, the old pirate was continually pursued by the law; the new pirate is not; he is as likely as not to be in Parliament making the law.

Greek Anthology 10.93

Greek Anthology 10.93 (by Palladas; tr. W.R. Paton):

It is better to endure even straitened FortuneThe same, tr. Tony Harrison:

rather than the arrogance of the wealthy.

Βέλτερόν ἐστι τύχης καὶ θλιβομένης ἀνέχεσθαι

ἢ τῶν πλουτούντων τῆς ὑπερηφανίης.

Just look at them, the shameless well-to-doLatin translation by Samuel Johnson:

and stop feeling sorry you're without a sou.

Fortunae malim adversae tolerare procellas,On the form of this couplet see Tobspruch.

Quam domini ingentis ferre supercilium.

Crabbe's Library

Not his poem "The Library," but his personal library, from The Life of George Crabbe By His Son (London: Oxford University Press, 1932), p. 250:

Another friend's library:

Would the reader like to follow my father into his library? — a scene of unparalleled confusion — windows rattling, paint in great request, books in every direction but the right — the table — but no, I cannot find terms to describe it, though the counterpart might be seen, perhaps, not one hundred miles from the study of the justly famed and beautiful rectory of Bremhill. Once, when we were staying at Trowbridge, in his absence for a few days at Bath, my eldest girl thought she should surprise and please him by putting every book in perfect order, making the best bound the most prominent; but, on his return, thanking her for her good intention, he replaced every volume in its former state; 'for,' said he, 'my dear, grandpapa understands his own confusion better than your order and neatness.'A friend's library:

Another friend's library:

Friday, October 27, 2017

Misoneism

Conall Cearnach (i.e. Frederick William O'Connell),"On Early Rising," The Age of Whitewash (Dublin: M.H. Gill & Son Ltd., 1921), pp. 108-111 (at 108):

I am a misoneist. Men of genius, Conservative politicians, lunatics, and savages are afflicted with misoneism. Therefore, since modesty will not permit of my claiming for myself a place among the first class, I prefer to include myself among the last. But what is misoneism? It is the Greek for "hatred of novelty"; an instinctive reluctance to adopt new-fangled notions, or to take advantage of modern inventions and conveniences.Greek has many compounds beginning with μισο-, but none of those compounds (so far as I can tell) end with elements meaning new (νέος, καινός). According to the Oxford English Dictionary, misoneism comes from Italian misoneismo (itself of course inspired by Greek).

Incurably Tedious Authors

E.R. Dodds (1893-1979), "The Rediscovery of the Classics," The Irish Statesman 2.42 (April 10, 1920) 346-347, rpt. as "The Classics and Classical Humbug," The Living Age, Vol. 305, No. 3961 (June 5, 1920) 607-609 (at 609):

Incurably tedious authors, such as Caesar, Xenophon, most of Livy, and Cicero and Demosthenes in their political speeches, should be expelled from the school curriculum. The schoolboy's staple fare might be drawn from the following: in Latin, Cicero pro Archia, pro Caelio, and pro Cluentio, Catullus, Apuleius, the letter writers, Tacitus, Vergil, and Lucretius; in Greek, Lucian, Herodotus, Homer, Euripides, Aristophanes, the myths of Plato, and the Anthology.

Thursday, October 26, 2017

Word-Chasing

Conall Cearnach (i.e. Frederick William O'Connell), "The Danger of the Dictionary," Old Wine & New (Dublin: M.H. Gill & Son Ltd., 1922), pp. 62-63:

Dictionaries are a delusion and a snare. Crede experto: in my time I have handled many. If anyone wants to know the real reason why I never got an exhibition in the Intermediate, it is simply because I acquired the (for me, at any rate) pernicious habit of frequenting the reading-room of the National Library in the evenings, ostensibly to study the Classics. Alas I there I was surrounded by temptation, for the walls were covered with dictionaries, and, once I succumbed to the lure of poring over one, the hours flew by, until closing time arrived without my ever opening my Greek or Latin text-book. Dictionaries seem to follow me wherever I go as stray dogs do kind-hearted people. There are at the present moment nineteen of them on my shelves, although I periodically try to lose them at secondhand book-stalls or give them away to learners.Related posts:

Of course, I should not like to part with my Dinneen. But that is different: I saw it in the making, being, so to speak, in at the birth. On the other hand, I feel that I owe whatever gleams of sanity remain with me to the fact that ten years ago I sold my large Liddell and Scott. To open that volume was to tempt Providence. Looking for one word found another of absorbing interest, and so on, until I was committed to a regular game of "send the fool farther." For a champion time-waster commend me to a Chinese dictionary. You start with the "word," which is a sort of post-impressionist sketch of a primitive picture. The first task in the solution of the picture-puzzle is to find the hidden "root," and when you have discovered it you painstakingly count the number of other strokes that go to make up the word—they may amount to twenty-two—and then, on looking in the dictionary under that particular root, plus the number of extra strokes, you find the meaning; that is, if you are not out in your count of the strokes, or have not started off with an imaginary root—a mistake which is not at all uncommon.

Some well-meaning individuals make it a practice to keep handy a dictionary of the vernacular for reference when writing letters, to be consulted in case of doubt. The fallacy underlying this is that people whose spelling is shaky are usually cocksure about the orthography of the very words which they invariably spell wrongly. Sometimes dictionaries try to escape notice, and deceive us as to their identity by describing themselves as Lexicons. For some reason or other, we talk of a Latin dictionary, but of a Greek or Hebrew "Lexicon." That is only another wile of the enemy of time.

Life is too short for word-chasing; and my advice to the prospective purchaser is, "Shun the lexicon as you would shun the very dictionary itself!" I am the least suspicious of mortals; yet, now that I come to think of it, most of my nineteen dictionaries (including lexicons) are presents! Just now it is fashionable in certain circles to evade the dog tax by judiciously losing the animal before the appointed day for registration. Can it be that I, in turn, have been the victim of the dictionary-"losing" game which I have so often played at the expense of other folk? If so, it is a righteous Nemesis.

Please Sit Down

G.K. Chesterton, Illustrated London News (March 17, 1928):

If I had a nice, neat, comfortable electric chair fitted up in my house ... I could quietly and quickly make a clearance of a great many ... social difficulties. It would be easy to receive a particular guest with gestures of hospitality; to wave him to a special seat with a special earnestness; to see him settled comfortably in it; and then to press a button with a smile and a sigh of relief.

Greek Anthology 9.400

Greek Anthology 9.400 (ascribed to Palladas; tr. W.R. Paton):

Latin translation by Hugo Grotius:

Revered Hypatia, ornament of learning, stainless star of wise teaching, when I see thee and thy discourse I worship thee, looking on the starry house of the Virgin; for thy business is in heaven.The rough breathing and acute accent are missing from the first letter of this poem in the Digital Loeb Classical Library, as the following screen capture shows:

Ὅταν βλέπω σε, προσκυνῶ, καὶ τοὺς λόγους,

τῆς παρθένου τὸν οἶκον ἀστρῷον βλέπων·

εἰς οὐρανὸν γάρ ἐστι σοῦ τὰ πράγματα,

Ὑπατία σεμνή, τῶν λόγων εὐμορφία,

ἄχραντον ἄστρον τῆς σοφῆς παιδεύσεως. 5

Latin translation by Hugo Grotius:

Colat necesse est literas, te qui videtJ.C. Wernsdorf, De Hypatia Philosopha Alexandrina (Wittenberg: Schlomach, 1747), p. 33 (after quoting Grotius' translation):

Et virginalem spectat astrigeram domum:

Negotium namque omne cum coelo tibi,

Hypatia prudens, dulce sermonis decus,

Sapientis artis sidus integerrimum.

Duos priores uersus sic mallem conuertere:Georg Luck, "Palladas: Christian or Pagan?" Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 63 (1958) 455-471 (at 462-467), argued that Palladas wasn't the author of this poem and that Hypatia here was someone other than the famous mathematician-philosopher. Alan Cameron, The Greek Anthology: From Meleager to Planudes (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993), pp. 323-325, apparently agreed with Luck and offered further arguments, although Cameron's book is unavailable to me. Opposed to Luck and Cameron are:

Te quando specto, te colo et uoces tuas

Et uirginalem specto sideream domum, etc.

- J. Irmscher, "Palladas und Hypatia (zu Anthologia Palatina 9.400)," in Acta Antiqua Philippopolitana: Studia Historica et Philologica (Sofia: In aedibus Typographicis Academiae Scientiarum Bulgaricae, 1963), pp. 313-318 (non vidi)

- Marc D. Lauxtermann, "The Palladas Sylloge," Mnemosyne 50.3 (June, 1997) 329-337 (at 335, n. 5)

- Enrico Livrea, "A.P. 9.400: Iscrizione funeraria di Ipazia?" Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 117 (1997) 99-102

- Henriette Harich-Schwarzbauer, Hypatia. Die spätantiken Quellen. Eingeleitet, kommentiert und interpretiert (Bern: Peter Lang, 2011), pp. 295-315 (non vidi)

Labels: typographical and other errors

Wednesday, October 25, 2017

Mental Derangement

Peter Heslin, "The Dream of a Universal Variorum: Digitizing the Commentary Tradition," in Christina S. Kraus and Christopher Stray, edd., Classical Commentaries: Explorations in a Scholarly Genre (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), pp. 494-511 (at 509):

An editor who removes a suspected interpolation may seem to do unforgivable violence to the author; if instead the reader were presented with a clickable button which permitted him or her to experiment with seeing the text with or without the suspect words, how much less a potential act of vandalism might this seem? How much less nastiness might there be in our little world? In its more toxic manifestations, textual criticism looks not so much an intellectual discipline as a mental derangement. Much of this is due to the inflexibility of movable type and the tyranny of the printed word, a situation alien to antiquity, and, increasingly, to us.

More Punishments in School

W.E. Heitland (1847-1935), After Many Years: A Tale of Experiences & Impressions Gathered in the Course of an Obscure Life (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1926), pp. 75-76 (at Shrewsbury):

The normal punishments formed a sort of tariff thusRelated posts:

(1) Penal Marks or 'Penals.' The unit was 50 lines from Paradise Lost. These had to be shewn up on Saturday, and each Monday the place for beginning was given out for the week, so that one could not write them on Sunday. The Punishments-master saw to this, and he sometimes accepted a number of Penals less than that due, on the ground of better handwriting.

(2) Two Penals = one 'Detention.' A Detention consisted in your being kept in half an hour after Second Lesson, from 12 to 12 30. You were supposed to spend the time learning by heart a fixed portion of the Latin Grammar, written in Latin as was then the fashion. On Tuesdays those 'detained' during the week were called up to repeat this to the Headmaster. Failure implied further punishment, but a tolerant management made this result rare.

(3) Two Detentions = one 'Idle List.' Idle List consisted in your being kept in for an hour at least, compelled to bring work and do it then and there. But you had no further liability once the period was over.

The detentive forms of punishment were both evils, but the 'Detentions' had no redeeming merit whatever. An old penalty of solitary confinement in a sort of dark cage had ceased to be used in my time, but there were traditions of its use not many years before. The cage, Butlerian (or earlier?) still stood in the Fifth Form room. I do not remember gating as a Shrewsbury punishment. Flogging was done with a 'birch' of broom-twigs. A monitor was in attendance to lift the culprit's shirt. It was the right thing for him to place himself so that the more pungent ends of the birch caught his trousered leg and minimized the designed effect. The ceremony was of rare occurrence. As a sincere and final penalty it had its merits.

- Plagosus Orbilius

- Inexpensive Instruments of Instruction

- A Close Connection Between the Skin and the Memory

- Et Nos Ergo Manum Ferulae Subduximus

- A Male Puberty Rite

- Anarchy Tempered by Despotism

- Punishment in School

Maurus the Rhetor, or a Moorish Rhetor?

Greek Anthology 11.204 (by Palladas; tr. W.R. Paton):

According to Liddell-Scott-Jones, ῥυγχελέφας, meaning "with an elephant's trunk," is a hapax legomenon.

Dudley Fitts, More Poems from the Palatine Anthology in English Paraphrase (New York: New Directions, 1941), page number unknown, poem number 41:

I was thunderstruck when I saw the rhetor Maurus, with a snout like an elephant, emitting a voice that murders one from lips weighing a pound each.Greek Anthology 16.20 (by Ammianus; tr. W.R. Paton):

Ῥήτορα Μαῦρον ἰδὼν ἐτεθήπεα, ῥυγχελέφαντα,

χείλεσι λιτραίοις φθόγγον ἱέντα φόνον.

I marvelled when I saw the rhetor Maurus, the heavy-lipped and white-robed demon of the art of Rhetoric.A.H.M. Jones et al., Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, Vol. I: A.D. 260-395 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971), p. 570:

Ῥήτορα Μαῦρον ἰδὼν ἀπεθαύμασα, τὸν βαρύχειλον,

τέχνης ῥητορικῆς δαίμονα λευκοφόρον.

Maurus (?) 3 rhetor L IV"H. Beckby ad loc." is Hermann Beckby, ed. and tr., Anthologia Graeca, Buch XII-XVI, 2nd rev. ed. (Munich: Ernst Heimeran Verlag, [1965]), p. 314.

Rhetor lampooned by Palladas; Egyptian, according to a lemma of dubious value, but to judge from the poems, a negro; cf. ῥυγχελέφαντα, χείλεσι λιτραίοις, in Anth. Gr. XI 204. 1-2, and βαρύχειλον, ib. XVI 20. 1 (ascribed to Palladas by H. Beckby ad loc.). Editors take Μαῦρος in both poems as a proper name, but it is probably an ethnic (a Moor).

According to Liddell-Scott-Jones, ῥυγχελέφας, meaning "with an elephant's trunk," is a hapax legomenon.

Dudley Fitts, More Poems from the Palatine Anthology in English Paraphrase (New York: New Directions, 1941), page number unknown, poem number 41:

Lo, I beheld Maurus,Palladas, Poems, a selection translated and introduced by Tony Harrison (London: Anvil Press Poetry, 1975), unpaginated, poem number 42, with the heading Maurus:

Professor of Public Speaking,

Raise high his elephant-snout

And from between his lips

(12 oz. apiece) give vent

To a voice whose very sound is accomplished murder.

I was impressed.

The politician's elephantine conk's

amazing, amazing too the voice that honks

through blubber lips (1 lb. net each)

spouting his loud, ear-shattering speech.

Tuesday, October 24, 2017

An Obscure Religious Sect

The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis, Books II and III. De Fide.

Second, revised edition. Translated by

Frank Williams (Leiden: Brill, 2013), p. 20:

14,4 They are called Tascodrugians for the following reason. Their word for "peg" is "tascus," and "drungus" is their word for "nostril" or "snout." And since they put their licking finger, as we call it, on their nostril when they pray, for dejection, if you please, and would-be righteousness, some people have given them the name of Tascodrugians, or "nose-pickers."75The Greek:

75 Filast. Haer. 76 appears to describe this group under the name of "Passalorinchitae." At Haer. 75 he speaks of "Ascodrugians," who dance wildly around an inflated wineskin.

καλοῦνται δὲ διὰ τοιαύτην αἰτίαν Τασκοδρουγῖται· τασκὸς παρ' αὐτοῖς πάσσαλος καλεῖται, δροῦγγος δὲ μυκτὴρ εἴτ' οὖν ῥύγχος καλεῖται, καὶ ἀπὸ τοῦ τιθέναι ἑαυτῶν τὸν δάκτυλον τὸν λεγόμενον λιχανὸν ἐπὶ τὸν μυκτῆρα ἐν τῷ εὔχεσθαι, δῆθεν κατηφείας χάριν καὶ ἐθελοδικαιοσύνης, ἐκλήθησαν ὑπό τινων Τασκοδρουγῖται τουτέστιν πασσαλορυγχῖται.See Christine Trevett, "Fingers up Noses and Pricking with Needles: Possible Reminiscences of Revelation in Later Montanism," Vigiliae Christianae 49.3 (August, 1995) 258-269.

How Can the State be Preserved?

Dio Cassius 56.7.5 (speech of Augustus; tr. Earnest Cary):

How otherwise can families continue? How can the State be preserved, if we neither marry nor have children? For surely you are not expecting men to spring up from the ground to succeed to your goods and to the public interests, as the myths describe! And yet it is neither right nor creditable that our race should cease, and the name of Romans be blotted out with us, and the city be given over to foreigners—Greeks or even barbarians.

πῶς μὲν γὰρ ἂν ἄλλως τὰ γένη διαμείνειε, πῶς δ᾿ ἂν τὸ κοινὸν διασωθείη μήτε γαμούντων ἡμῶν μήτε παιδοποιουμένων; οὐ γάρ που καὶ ἐκ τῆς γῆς προσδοκᾶτέ τινας ἀναφύσεσθαι τοὺς διαδεξομένους τά τε ὑμέτερα καὶ τὰ δημόσια, ὥσπερ οἱ μῦθοι λέγουσιν. οὐ μὴν οὐδ᾿ ὅσιον ἢ καὶ καλῶς ἔχον ἐστὶ τὸ μὲν ἡμέτερον γένος παύσασθαι καὶ τὸ ὄνομα τὸ Ῥωμαίων ἐν ἡμῖν ἀποσβῆναι, ἄλλοις δέ τισιν ἀνθρώποις Ἕλλησιν ἢ καὶ βαρβάροις τὴν πόλιν ἐκδοθῆναι.

A Caricature of Man

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), The Will to Power, § 397 (tr. Walter Kaufmann and R.J. Hollingdale):

Man, imprisoned in an iron cage of errors, became a caricature of man, sick, wretched, ill-disposed toward himself, full of hatred for the impulses of life, full of distrust of all that is beautiful and happy in life, a walking picture of misery: this artificial, arbitrary, recent abortion that the priests have pulled up out of their soil, the "sinner": how shall we be able, in spite of all, to justify this phenomenon?

Der Mensch, eingesperrt in einen eisernen Käfig von Irrthümern, eine Caricatur des Menschen geworden, krank, kümmerlich, gegen sich selbst böswillig, voller Haß auf die Antriebe zum Leben, voller Mißtrauen gegen Alles, was schön und glücklich ist am Leben, ein wandelndes Elend: diese künstliche, willkürliche, nachträgliche Mißgeburt, welche die Priester aus ihrem Boden gezogen haben, den »Sünder«: wie werden wir es erlangen, dieses Phänomen trotz alledem zu rechtfertigen?

Amoebaeic

The Oxford English Dictionary has an entry for amœbaean, adj. = "Alternately answering, responsive," but not for amoebaeic, a word I first encountered in P. Vergili Maronis Bucolica et Georgica. With Introduction and Notes by T.E. Page (1898; rpt. London: Macmillan, 1968), p. 111 (introduction to Eclogue 3):

Such poetry as verses 60-107 was called Amoebaeic (ἀμοιβαία ἀοιδά Theocr. 8.31) from ἀμοιβή 'interchange,' and Virgil calls it 'alternate song' (alterna line 59). The rule was that the second singer should answer the first in an equal number of verses, on the same or a similar subject, and also if possible show superior force or power of expression, or, as we say, 'cap' what the first had said. The 9th Ode of the Third Book of Horace's Odes is a perfect specimen of this kind of verse.But Page wasn't the first to use amoebaeic in English. The word occurs on ten different pages in Thomas Keightley, Notes on the Bucolics and Georgics of Virgil (London: Whittaker and Co., 1846), always as amœbæic. I see the word in four JSTOR articles (one by Page), and over a hundred times in Google Books.

Labels: lexicography

Monday, October 23, 2017

Busy in Their Own Eyes

Vauvenargues (1715-1747), Reflections and Maxims, no. 118 (tr. F.G. Stevens):

The man who is always lunching or dining out imagines he is busy, and he who spends his morning in cleaning his teeth and receiving his tailor mocks the idleness of the gossip who takes a walk every day before lunch.

Un homme qui ne dîne ni ne soupe chez soi, se croit occupé, et celui qui passe la matinée à se laver la bouche, et à donner audience à son brodeur, se moque de l'oisiveté d'un nouvelliste, qui se promène tous les jours avant dîner.

Mumchance's the Word

I've often heard the expression "Mum's the word," but until recently the word "mumchance" was unknown to me. Oxford English Dictionary s.v. mumchance, v.:

Related posts:

1. intr. To masquerade. Obs. rare.Id., s.v. mumchance, n. and adj.:

2. intr. Eng. regional. To keep silent, to remain sullenly silent.

A. n."A person who has nothing to say" — that describes me perfectly. Michael Mumchance.

1. (a) A dice game resembling hazard. Now hist. (b) In extended use: a chance, a hazardous venture (cf. HAZARD n. and adj. Phrases 2). Now Eng. regional (rare).

2. Silence. to play mumchance: to keep a dogged silence. Obs.

3. Sc. Masquerade; mumming. Obs.

4. A person who acts in a mime or dumbshow; (hence) a person who has nothing to say. Also used as a nickname, or as the type of a silent person. Now Eng. regional.

B. adj.

Silent, mute; tongue-tied. Frequently in to sit (also stand, etc.) mumchance.

Related posts:

- Men of Few Words

- Acanthian Cicada

- Taciturn in Seven Ancient Languages

- Character of a Taciturn Person

- Silent in Seven Languages

- Unfit for the Society of the Living

- Burton's Characters

- Unit of Taciturnity: The Dirac

- Ich bin ein Boeotier

- The Merest Statue of a Man

- One of the Most Ungregarious of Beings

- Small Talk

- Penury of Words

- Portrait of a Shy Man

The Logic of Plautus

Paul Lejay (1861-1920), Plaute (Paris: Boivin, 1925), p. 216 (my translation):

Since one sees that the logic of Leo isn't that of Ribbeck and that the logic of Ribbeck isn't that of Ritschl (to mention only the Grand Poobahs), there is the possibility that the logic of Plautus wasn't that of Ritschl, Ribbeck, or Leo.Mutatis mutandis, this could be said of many ancient writers and modern scholars. I haven't seen Lejay's Plaute, just this quotation.

Comme on voit que la logique de Léo n'est pas celle de Ribbeck et que la logique de Ribbeck n'est pas celle de Ritschl, pour ne citer que les grands dieux, il y a des chances pour que la logique de Plaute n'ait été ni celle de Ritschl, ni celle de Ribbeck, ni celle de Léo.

Sunday, October 22, 2017

Punishment in School

Mandell Creighton, quoted in

Life and Letters of Mandell Creighton, D.D. Oxon. and Cam., Sometime Bishop of London. By His Wife, Vol. I (Longmans, Green and Co., 1906), p. 14:

[From Joel Eidsath:

Dear Mike,

Ouch! It was as bad at home. Here is a passage from the memoirs of Creighton's wife:

As ever,

Ian [Jackson]

Related posts:

As regards punishment, I strongly recommend giving a fellow a thrashing, the fellows like it best themselves—better than setting impositions or reporting. Setting impositions is essentially weak, and shams master too much: I should only recommend it in the case of fellows so little, or so weak, you did not like to thrash them, or as an addition to a thrashing when you felt the latter was not enough. For drunkenness and beastliness (also for bullying and stealing, of course) thrash a fellow at once, as hard as ever you like—you cannot give him too much; but let me recommend that no fellow be thrashed by any of you hastily or in a passion, but that before thrashing a fellow you consult some of your brother monitors. Remember, never thrash a fellow a little, always hard: and it is always well that he be thrashed by more than one of the monitors.If this were a classical text, I might obelize "shams master," as I suspect it is corrupt.

[From Joel Eidsath:

I would have to protest your obelization. "Shams" could be the verb "to sham" in the sense of "to sham illness". The advice is given to a monitor, and the Bishop refers to, I believe, an action that savors of a monitor acting as a sham master towards the other boys.]When I was in seventh grade, a teacher slammed me against a locker in the hallway. I hadn't done anything wrong, but I didn't protest because:

1) On many other occasions I had done something wrong, without being caught.

2) If I had complained to my parents, they would have punished me a second time. Teachers, in the opinion of my parents, were always in the right.

Dear Mike,

Ouch! It was as bad at home. Here is a passage from the memoirs of Creighton's wife:

I do not think that I had much difficulty in managing the children, though of course there was a good deal of quarrelling & temper at times. I tried to make punishments fit the offense as Herbert Spencer enjoined, & I always objected to anything of the nature of a judicial punishment. Some of my punishments may be considered brutal by some people. Cuthbert was a very mischievous boy, & used to play with fire & cut things with knives, so when he played with fire I held his finger on the bar of the grate for a minute that he might feel how fire burnt, & when he cut woodwork with his knife I gave his fingers a little cut. I never whipt any child.Memoirs of a Victorian Woman: Reflections of Louise Creighton, 1850-1936, edited with introduction and annotation by James Thayne Covert (Indiana University Press, 1994), p.72.

As ever,

Ian [Jackson]

Related posts:

- Plagosus Orbilius

- Inexpensive Instruments of Instruction

- A Close Connection Between the Skin and the Memory

- Et Nos Ergo Manum Ferulae Subduximus

- A Male Puberty Rite

- Anarchy Tempered by Despotism

The Learned and the Foolish

Quintilian 10.7.22 (tr. Donald A. Russell):

If you quote this saying of Quintilian as it appears in the Routledge Dictionary, you will truly be exposed as illiterate.

Those who want to seem learned to the foolish seem fools to the learned.The Latin is mangled in Jon R. Stone, The Routledge Dictionary of Latin Quotations: The Illiterati's Guide to Latin Maxims, Mottoes, Proverbs, and Sayings (New York: Routledge, 2005), p. 97:

qui stultis videri eruditi volunt, stulti eruditis videntur.

If you quote this saying of Quintilian as it appears in the Routledge Dictionary, you will truly be exposed as illiterate.

Labels: typographical and other errors

One of Life's Pleasures

Dean Inge, quoted by Geoffrey Madan, Notebooks: A Selection, edd. J.A. Gere and John Sparrow (1981; rpt. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985), p. 135:

Perhaps the most lasting pleasure in life is the pleasure of not going to church.

Saturday, October 21, 2017

Carpe Diem

Theognis 983–988 (tr. Douglas E. Gerber):

Let us give up our hearts to festivity, while they can still sustain pleasure's lovely activities. For the splendour of youth passes by as quickly as a thought. Not so swift are charging horses which, delighting in the wheat-bearing plain, carry their spear-wielding master furiously to the battle toil of men.The same, tr. Andrew M. Miller:

ἡμεῖς δ᾿ ἐν θαλίῃσι φίλον καταθώμεθα θυμόν,

ὄφρ᾿ ἔτι τερπωλῆς ἔργ᾿ ἐρατεινὰ φέρῃ.

αἶψα γὰρ ὥστε νόημα παρέρχεται ἀγλαὸς ἥβη· 985

οὐδ᾿ ἵππων ὁρμὴ γίνεται ὠκυτέρη,

αἵ τε ἄνακτα φέρουσι δορυσσόον ἐς πόνον ἀνδρῶν

λάβρως, πυροφόρῳ τερπόμεναι πεδίῳ.

Let us devote our hearts to merriment and feastingI'm not sure who translated these lines in The Cambridge History of Classical Literature, I: Greek Literature, edd. P.E. Easterling and B.M.W. Knox (Cambridge: Cambridge Univerity Press, 1985; rpt. 2003), pp. 141-142:

while the enjoyment of delights still brings pleasure.

For quick as thought does radiant youth pass by,

nor does the rush of horses prove to be swifter

when carrying their master to the labor of men's spears

with furious energy, taking joy in the plain that brings forth wheat.

As for us, let us devote our hearts to feast and celebration, while they can still feel the joy of pleasure's motions. For glorious youth passes by swift as a thought, swifter than the burst of speed shown by horses as they take a chieftain and his spear to the battle line, galloping furiously as they take their joy in the flatness of the wheatfields.T. Hudson-Williams ad loc.:

Friday, October 20, 2017

The Future, Accurately Predicted

G.K. Chesterton, Illustrated London News (December 16, 1911):

If I wrote a romance about the future (which Heaven avert!), I should describe a state in which the big shops and businesses had become almost independent kingdoms or clans, the power of the employer over clerks and shopmen enormous; the power of the State over the employer comparatively slight.G.K. Chesterton, Illustrated London News (June 9, 1934):

I have not the slightest difficulty in imagining the world of the future taking a turn which would bring back the fact, if not the form, of witch-hunting and slavery and the persecution of heresies.

Leave the Rest to Fate

Greek Anthology 11.62 (by Palladas, tr. Tony Harrison):

Related post: Make Thee Merry.

Death's a debt that everybody owes,R. Kassel, "Dichterspiele," Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 42 (1981) 11-20 (at 17, n. 34), regards this as a paraphrase of Euripides, Alcestis 782-789, here in the translation of Moses Hadas and John McLean:

and if you'll last the night out no-one knows.

Learn your lesson then, and thank your stars

for wine and company and all-night bars.

Life careers gravewards at a breakneck rate,

so drink and love, and leave the rest to Fate.

πᾶσι θανεῖν μερόπεσσιν ὀφείλεται, οὐδέ τις ἐστὶν

αὔριον εἰ ζήσει θνητὸς ἐπιστάμενος.

τοῦτο σαφῶς, ἄνθρωπε, μαθὼν εὔφραινε σεαυτόν,

λήθην τοῦ θανάτου τὸν Βρόμιον κατέχων.

τέρπεο καὶ Παφίῃ, τὸν ἐφημέριον βίον ἕλκων·

τἄλλα δὲ πάντα Τύχῃ πράγματα δὸς διέπειν.

All men have to pay the debt of death,The similarity was also noticed by others, e.g. Bruno Lier, "Topica carminum sepulcralium latinorum. Pars II," Philologus 62 (1903) 563-603 (at 582-583).

and there is not a mortal who knows

whether he is going to be alive on the morrow.

The outcome of things that depend on fortune cannot be foreseen;

they can neither be learnt nor discovered by any art.

Hearken to this and learn of me,

cheer up, drink, reckon the days

yours as you live them; the rest belongs to fortune.

βροτοῖς ἅπασι κατθανεῖν ὀφείλεται,

κοὐκ ἔστι θνητῶν ὅστις ἐξεπίσταται

τὴν αὔριον μέλλουσαν εἰ βιώσεται·

τὸ τῆς τύχης γὰρ ἀφανὲς οἷ προβήσεται, 785

κἄστ᾿ οὐ διδακτὸν οὐδ᾿ ἁλίσκεται τέχνῃ.

ταῦτ᾿ οὖν ἀκούσας καὶ μαθὼν ἐμοῦ πάρα

εὔφραινε σαυτόν, πῖνε, τὸν καθ᾿ ἡμέραν

βίον λογίζου σόν, τὰ δ᾿ ἄλλα τῆς τύχης.

Related post: Make Thee Merry.

Thursday, October 19, 2017

Two Pains

Greek Anthology 12.172 (by Euenus; tr. W.R. Paton):

The same, tr. Alistair Elliot:

If to hate is pain and to love is pain, of the two evilsGreek ἕλκος is cognate with Latin ulcus, -eris.

I choose the smart of kind pain.

εἰ μισεῖν πόνος ἐστί, φιλεῖν πόνος, ἐκ δύο λυγρῶν

αἱροῦμαι χρηστῆς ἕλκος ἔχειν ὀδύνης.

The same, tr. Alistair Elliot:

If hate is painful and if love's a pain,The same, tr. Daryl Hine:

I'll choose the wound that is not quite in vain.

Since hating's a bore and loving is a bore,

I like the nicer of two boredoms more.

People in Greece and Rome

The Way It Wasn't: From the Files of James Laughlin (New York: New Directions, 2006), p. 36 (under the heading "Brown University"):

My students range from tops to, well, what do you think of this little miss, who ended her paper: "We cannot say that Pound's 'Mauberley' is a work of art because he writes about so many people in Greece and Rome who nobody knows anything about any more. Pound could not have written this poem without Froula's guide.""Froula's guide" = Christine Froula, A Guide to Ezra Pound's Selected Poems (New York: New Directions, 1983)!

Nocturnal Misadventure

Martin L. West (1937-2015), Greek Elegy and Iambus (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1974), p. 172 (on [Homer,] Margites, fragment 7 = P.Oxy. 2309):

The verses describe a comic nocturnal misadventure — no doubt of Margites — conceived in a spirit of Hipponactean farce. (Line 3 indeed parallels Hippon. 92.6.) I take the narrative to run as follows. Needing to empty his bladder (1?), he pushes the appropriate organ into a vessel, and finds he is stuck, hand and all (1-5). In this predicament he promptly passes water (6). Now he has another idea. He leaves his bed and rushes out into the night, looking for means to free his hand (7-11). It is pitch dark; he has no torch (12-13). Encountering the unlucky head of some other person, he takes it for a stone, and with one hefty blow he smashes the pot over it (14-17), thus administering at once a painful crack on the pate and a sour douche.

Son Criticizes Father's Appearance

Homer, Odyssey 24.248-250 (Odysseus to Laertes; tr. Richmond Lattimore):

But I will also tell you this; do not take it as cause for

anger. You yourself are ill cared for; together with dismal

old age, which is yours, you are squalid and wear foul clothing upon you.

ἄλλο δέ τοι ἐρέω, σὺ δὲ μὴ χόλον ἔνθεο θυμῷ·

αὐτόν σ᾿ οὐκ ἀγαθὴ κομιδὴ ἔχει, ἀλλ᾿ ἅμα γῆρας

λυγρὸν ἔχεις αὐχμεῖς τε κακῶς καὶ ἀεικέα ἕσσαι.

Wednesday, October 18, 2017

Fate of Scholarly Journals

The Way It Wasn't: From the Files of James Laughlin (New York: New Directions, 2006), p. 36:

dokuku = documentary (see below)

ouragon = hurricane

Dear Mike,

My guess is that "dokuku" is Laughlinese for "documentary". You'll note from his Paris Review interview (1983) that he was involved with the series of documentaries on American poets produced by the New York Center for Visual History:

https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/3015/james-laughlin-the-art-of-publishing-no-1-part-2-james-laughlin

At that point they were concerned with Ezra Pound, but the entire series of "Voices & Visions" did eventually air on PBS in 1988. The 13th and last programme was devoted to William Carlos Williams. I've not seen it, though it can be watched online at no charge on the Annenberg Foundation website:

http://www.learner.org/resources/series57.html#

If it includes Laughlin interviewing Kenneth Burke, which (if Burke was 88) must have been in 1985, I'd say the case is closed, and even if not, JL and KB could have been left on the cutting room floor.

As ever,

Ian [Jackson]

Related posts:

Do you know Kenneth Burke? We went out there to interview him for the WCW dokuku. 88 and all bent over but what an ouragon of passion for ideas and language. He's lived on the same farm in New Jersey for over 60 years. His daughters made him put in plumbing but he still uses the old privy in summer. Pages from learned journals for bumwad. And I have shat / where that great mind sat.WCW = William Carlos Williams

dokuku = documentary (see below)

ouragon = hurricane

Dear Mike,

My guess is that "dokuku" is Laughlinese for "documentary". You'll note from his Paris Review interview (1983) that he was involved with the series of documentaries on American poets produced by the New York Center for Visual History:

https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/3015/james-laughlin-the-art-of-publishing-no-1-part-2-james-laughlin

At that point they were concerned with Ezra Pound, but the entire series of "Voices & Visions" did eventually air on PBS in 1988. The 13th and last programme was devoted to William Carlos Williams. I've not seen it, though it can be watched online at no charge on the Annenberg Foundation website:

http://www.learner.org/resources/series57.html#

If it includes Laughlin interviewing Kenneth Burke, which (if Burke was 88) must have been in 1985, I'd say the case is closed, and even if not, JL and KB could have been left on the cutting room floor.

As ever,

Ian [Jackson]

Related posts:

- An Ignominious End

- Yet More Bumf

- Fate of Ancient Authors

- A Capital Offence

- A Most Painful Subject

- An Episode in the History of Bumf

- Die Arschwische

- Bumf

- Bumf Again

- More Bumf

- Cacata Carta

- Bumf in Coleridge

- A Place for Reading

- Books and Toilets

Labels: noctes scatologicae

Rum Thing

Peter Brown, "Dialogue With God," New York Review of Books (October 26, 2017), a review of Sarah Ruden's translation of Augustine, Confessions:

He spends a large part of book two (nine entire pages) examining his motives for robbing a pear tree. Modern readers chafe. "Rum thing," wrote Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes to Harold Laski in 1921, "to see a man making a mountain out of robbing a pear tree in his teens."

But Holmes was wrong to be impatient. Only by winnowing every motive that played into that obscure act of small-town vandalism was Augustine able to isolate the very smallest, the most toxic concentrate of all—the chilling possibility that he had acted gratuitously, simply to show that he (like God, and then like Adam) could do whatever he wished. The publishers were right to put on the jacket of this book, which contains a succession of sins, each reduced to chillingly minute proportions, the image of a half-eaten pear.

Cause for Rejoicing

Homer, Odyssey 23.47-48 (Eurycleia to Penelope, "him" = Odysseus; tr. A.T. Murray, rev. George E. Dimock):

Alfred Heubeck in his commentary on line 48:

The sight of him would have warmed your heart with cheer,λύθρον isn't filth in general but rather "defilement from blood, gore" (Liddell-Scott-Jones).

all befouled with blood and filth like a lion.

ἰδοῦσά κε θυμὸν ἰάνθης

αἵματι καὶ λύθρῳ πεπαλαγμένον, ὥς τε λέοντα.

Alfred Heubeck in his commentary on line 48:

= xxii 402. This line, omitted in many MSS, is considered by a number of editors and critics (among them Ameis-Hentze-Cauer; von der Mühll, Odyssee, col, 761; W. Schadewaldt, op. cit. (Introd.), 15 n. 9) to be a late interpolation, largely on account of its 'unseemliness', which may already have led to its athetesis by the Alexandrian critics (which then influenced the MS tradition). Such purely subjective arguments can, however, lead to false conclusions. Here it must be borne in mind that the speaker is Eurycleia who earlier had herself been moved to jubilation by the sight of the dead suitors (xxii 407 ff.: ἴθυσέν ῥ' όλολύξαι). For the authenticity of the line cf. Stanford, ad loc.; van der Valk, Textual Criticism, 271; G. Scheibner, DLZ lxxxii (1961), col. 622 ('xxiii 48 recalls once again the description of xxii 204 [sic, read 402] ff.').I'm also reminded of Hector's prayer for his son (Homer, Iliad 6.480-481, tr. Richmond Lattimore):

... and let him kill his enemy

and bring home the blooded spoils, and delight the heart of his mother.

φέροι δ᾽ ἔναρα βροτόεντα

κτείνας δήϊον ἄνδρα, χαρείη δὲ φρένα μήτηρ.

Tuesday, October 17, 2017

You Young Puppies!

The Way It Wasn't: From the Files of James Laughlin (New York: New Directions, 2006), p. 86:

Were it not for Dudley Fitts, my English master at Choate, I would never have become a scribbler, nor for that matter a publisher. For it was Fitts, in correspondence with Pound, who arranged for me to study at the "Ezuversity" in Rapallo. And Pound, descrying no talent for poetry, ordained that I become a publisher.Hat tip: Ian Jackson.

Fitts was a handsome but slightly odd-looking man. He couldn't see much without his horn-rimmed glasses, but that wasn't it. Finally, as I observed him in class, it came to me. His forehead. His brow was higher by three eighths of an inch than that of anyone else in the room. He was indeed a highbrow.

My first brief conversation with him is forever etched, as they say, on the plate of memory. As an underformer I had seen him around, but had never been assigned — we were rotated every two weeks — to his table in the dining hall. One day when I was rushing up the stairs from the mail room and he was coming down wearing the black Dracula cape which he affected, I bumped into him and knocked him half down. The irate gaze of Hermes was fixed upon me and he uttered: "You young puppies who haven't even read Thucydides!" And the God continued on his errand.

How Few Boys Relish Latin and Greek Lessons!

Benjamin Rush (1746-1813), "Observations upon the study of the Latin and Greek languages, as a branch of liberal education, with hints of a plan of liberal instruction, without them, accommodated to the present state of society, manners, and government in the United States," Essays, Literary, Moral and Philosophical, 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: Thomas and William Bradford, 1806), pp. 21-56 (at 23):

The famous Busby is said to have died of "bad Latin;" that is, the ungrammatical versions of his scholars broke his heart. How few boys relish Latin and Greek lessons! The pleasure they sometimes discover in learning them, is derived either from the tales they read, or from a competition, which awakens a love of honour, and which might be displayed upon a hundred more useful subjects; or it may arise from a desire of gaining the good will of their masters or parents. Where these incentives are wanting, how bitter does the study of languages render that innocent period of life, which seems exclusively intended for happiness! "I wish I had never been born," said a boy of eleven years old, to his mother: "Why, my son?" said his mother. "Because I am born into a world of trouble." "What trouble," said his mother smiling, "have you known, my son?" — "Trouble enough, mamma," said he, "two Latin lessons to get, every day."Id. (at 24):

The study of some of the Latin and Greek classics is unfavourable to morals and religion. Indelicate amours, and shocking vices both of gods and men, fill many parts of them. Hence an early and dangerous acquaintance with vice; and hence, from an association of ideas, a diminished respect for the unity and perfection of the true God.Id. (at 34):

Happy will it be for the present and future generations, if an ignorance of the Latin and Greek languages, should banish from modern poetry, those disgraceful invocations of heathen gods, which indicate no less a want of genius, than a want of reverence for the true God.Id. (at 39):

We occupy a new country. Our principal business should be to explore and apply its resources, all of which press us to enterprize and haste. Under these circumstances, to spend four or five years in learning two dead languages, is to turn our backs upon a gold mine, in order to amuse ourselves in catching butterflies.Id. (at 43, discussing "the advantages [that] would immediately attend the rejection of the Latin and Greek languages as branches of a liberal education"):

It would be the means of banishing pride from our seminaries of public education. Men are generally most proud of those things that do not contribute to the happiness of themselves, or others. Useful knowledge generally humbles the mind, but learning, like fine clothes, feeds pride, and thereby hardens the human heart.

Song of Benediction

Friedrich Solmsen, "Aeschylus: The Eumenides," Hesiod and Aeschylus (1949; rpt. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1995), pp. 178-224 (at 211-212, footnotes omitted):

The song of benediction is one of the old forms of religious poetry which Aeschylus embodied in his tragedy. Like the hymns, γόοι and θρῆνοι, it is a 'ritual' feature, a reminder to us of the fundamentally religious character of tragedy which to its first great poet was still a vividly felt reality. For the spectators of the original performance the songs and blessings pronounced in such a solemn form and on such a solemn occasion must have carried a strong conviction of fulfillment.D.S. Carne-Ross, "The Beastly House of Atreus," Kenyon Review 3.2 (Spring, 1981) 20-60 (at 54):

The first stanza promises in general terms 'helpful wavelets of livelihood gushing forth,' a boon which is made specific by the wish that the shining light of the Sun will produce them from the earth. Thus we know to what kind of wealth allusion is made. The next stanza elaborates this source of blessing, announcing absence of anything that may harm the plants, promising prosperity of the flocks and rich gifts from the mines. The Furies also banish from Attic territory sickness and disease that may intercept the youth in their growth to manhood and maturity, and for the maidens in particular they desire that they shall reach their natural goal of marriage. The last stanza alone has a bearing upon the political situation. It promises that civic strife and the slaughter and bloodshed that accompany it will not visit Athens and hopes that the citizens will be united in their loves and hatreds. Evidently it would be utopian, and it would perhaps never occur to Aeschylus, to expect that hatred might altogether be extirpated in the community. Like fear and awe it is a part of the material that the lawgiver or statesman has to fashion, and the best that he can hope to achieve is to give their loves and hatreds identical objects or directions.

Through the words of the Furies' final song of blessing, all that remains of a greater whole, there breathes a note of solemn and yet festive joy as of a Bach chorale.Aeschylus, Eumenides 902-909 (tr. Alan H. Sommerstein):

CHORUSId. 922-926:

So what blessings do you bid me invoke upon this land?

ATHENA

Such as are appropriate to an honourable victory, coming moreover both from the earth, and from the waters of the sea, and from the heavens; and for the gales of wind to come over the land breathing the air of bright sunshine; and for the fruitfulness of the citizens' land and livestock to thrive in abundance, and not to fail with the passage of time; and for the preservation of human seed.

ΧΟΡΟΣ

τί οὖν μ᾿ ἄνωγας τῇδ᾿ ἐφυμνῆσαι χθονί;

ΑΘΗΝΑΙΑ

ὁποῖα νίκης μὴ κακῆς ἐπίσκοπα,

καὶ ταῦτα γῆθεν ἔκ τε ποντίας δρόσου

ἐξ οὐρανοῦ τε· κἀνέμων ἀήματα 905

εὐηλίως πνέοντ᾿ ἐπιστείχειν χθόνα·

καρπόν τε γαίας καὶ βοτῶν ἐπίρρυτον

ἀστοῖσιν εὐθενοῦντα μὴ κάμνειν χρόνῳ·

καὶ τῶν βροτείων σπερμάτων σωτηρίαν.

For which city I pray,Id. 938-948:

and prophesy with kind intent,

that the bright light of the sun

may cause blessings beneficial to her life

to burst forth in profusion from the earth.

ᾇ τ᾿ ἐγὼ κατεύχομαι

θεσπίσασα πρευμενῶς

ἐπισσύτους βίου τύχας ὀνησίμους

γαίας ἐξαμβρῦσαι 925

φαιδρὸν ἁλίου σέλας.

And may no wind bringing harm to trees —Id. 977-987:

I declare my own gracious gift —

blow scorching heat that robs plants of their buds:

let that not pass the borders of the land.

Nor let any grievous, crop-destroying

plague come upon them;

may their flocks flourish, and may Pan

rear them to bear twin young

at the appointed time; and may their offspring always

have riches in their soil, and repay

the lucky find granted them by the gods.

δενδροπήμων δὲ μὴ πνέοι βλάβα —

τὰν ἐμὰν χάριν λέγω —

φλογμοὺς ὀμματοστερεῖς φυτῶν, 940

τὸ μὴ περᾶν ὅρον τόπων·

μηδ᾿ ἄκαρπος αἰα-

νὴς ἐφερπέτω νόσος·

μῆλα δ᾿ εὐθενοῦντα Πὰν

ξὺν διπλοῖσιν ἐμβρύοις 945

τρέφοι χρόνῳ τεταγμένῳ· γόνος <δ᾿ ἀεὶ>

πλουτόχθων ἑρμαίαν

δαιμόνων δόσιν τίνοι.

I pray that civil strife,

insatiate of evil,

may never rage in this city;

and may the dust not drink up the dark blood of the citizens

and then, out of lust for revenge,

eagerly welcome the city's ruin

through retaliatory murder;

rather may they give happiness in return for happiness,

resolved to be united in their friendship

and unanimous in their enmity;

for this is a cure for many ills among men.

τὰν δ᾿ ἄπληστον κακῶν

μήποτ᾿ ἐν πόλει στάσιν

τᾷδ᾿ ἐπεύχομαι βρέμειν,

μηδὲ πιοῦσα κόνις μέλαν αἷμα πολιτᾶν 980

δι᾿ ὀργὰν ποινᾶς

ἀντιφόνους ἄτας

ἁρπαλίσαι πόλεως·

χάρματα δ᾿ ἀντιδιδοῖεν

κοινοφιλεῖ διανοίᾳ 985

καὶ στυγεῖν μιᾷ φρενί·

πολλῶν γὰρ τόδ᾿ ἐν βροτοῖς ἄκος.

Monday, October 16, 2017

Four-Fold Remedies

The Epicureans had their four-fold remedy, their τετραφάρμακος (tetrapharmakos):

I haven't seen Ignazio Cazzaniga, "Il tetrapharmacum cibo adrianeo (H.A. Spart., Vit. Hadr. 21, 4, Vit. Ael. 5, 4 e Philod. P. Herc. 1005, IV, 10). Esegesi e critica testuale," in Poesia latina in frammenti (Genoa: Università di Genova, Facoltà di lettere, Istituto di filologia classica e medievale, 1974), pp. 359-366.

Celsus in his treatise on medicine (5.19.9) mentions a plaster made of four ingredients (wax, pitch, resin, and beef suet) "called by the Greeks tetrapharmacon."

A friend of mine calls the Historia Augusta the ancient equivalent of "fake news," but I'm finding it interesting reading, when taken with a grain of salt. I wonder if anyone in modern times has cooked and eaten pheasant, sow's udders, and ham en croûte.

Related post: The Epicurean Tetrapharmakos.

Not to be feared—god,Less spiritual, but still fortifying the inner man, was the dish called tetrapharmacum (Historia Augusta, 1: Life of Hadrian 21.4, tr. David Magie):

not to be viewed with apprehension—death;

and on the one hand, the good—easily acquired,

on the other hand, the terrible—easily endured.

ἄφοβον ὁ θεός,

ἀνύποπτον ὁ θάνατος,

καὶ τἀγαθὸν μὲν εὔκτητον,

τὸ δὲ δεινὸν εὐεκκαρτέρητον.

As an article of food he was singularly fond of tetrapharmacum, which consisted of pheasant, sow's udders, ham, and pastry.Cf. Historia Augusta, 2: Life of Aelius 5.4-5 (tr. David Magie):

inter cibos unice amavit tetrapharmacum, quod erat de phasiano sumine perna et crustulo.

For it is Verus who is said to have been the inventor of the tetrapharmacum, or rather pentapharmacum, of which Hadrian was thereafter always fond, namely, a mixture of sows' udders, pheasant, peacock, ham in pastry and wild boar. Of this article of food Marius Maximus gives a different account, for he calls it, not pentapharmacum, but tetrapharmacum, as we have ourselves described it in our biography of Hadrian.and Historia Augusta, 18: Life of Severus Alexander 30.6 (tr. David Magie):

nam tetrapharmacum, seu potius pentapharmacum, quo postea semper Hadrianus est usus, ipse dicitur repperisse, hoc est sumen phasianum pavonem pernam crustulatam et aprunam. de quo genere cibi aliter refert Marius Maximus, non pentapharmacum sed tetrapharmacum appellans, ut et nos ipsi in eius vita persecuti sumus.

And he often partook of Hadrian's tetrapharmacum, which Marius Maximus describes in his work on the life of Hadrian.In the Digital Loeb Classical Library, this last passage is corrupt (Maximum instead of Maximus), both in the Latin and the English (the printed book is correct):

ususque est Hadriani tetrapharmaco frequenter, de quo in libris suis Marius Maximus loquitur, cum Hadriani disserit vitam.

I haven't seen Ignazio Cazzaniga, "Il tetrapharmacum cibo adrianeo (H.A. Spart., Vit. Hadr. 21, 4, Vit. Ael. 5, 4 e Philod. P. Herc. 1005, IV, 10). Esegesi e critica testuale," in Poesia latina in frammenti (Genoa: Università di Genova, Facoltà di lettere, Istituto di filologia classica e medievale, 1974), pp. 359-366.

Celsus in his treatise on medicine (5.19.9) mentions a plaster made of four ingredients (wax, pitch, resin, and beef suet) "called by the Greeks tetrapharmacon."

A friend of mine calls the Historia Augusta the ancient equivalent of "fake news," but I'm finding it interesting reading, when taken with a grain of salt. I wonder if anyone in modern times has cooked and eaten pheasant, sow's udders, and ham en croûte.

Related post: The Epicurean Tetrapharmakos.

Labels: typographical and other errors

Sunday, October 15, 2017

Rottenness

Marcus Aurelius, Meditations 9.36 (tr. A.S.L. Farquharson):

The rottenness of the matter which underlies everything. Water, dust, bones, stench.

τὸ σαπρὸν τῆς ἑκάστῳ ὑποκειμένης ὕλης· ὕδωρ, κόνις, ὀστάρια, γράσος.

Bread and Circuses

Étienne de La Boétie (1530-1563), Discourse on Voluntary Servitude (tr. Harry Kurz):

Plays, farces, spectacles, gladiators, strange beasts, medals, pictures, and other such opiates, these were for ancient peoples the bait toward slavery, the price of their liberty, the instruments of tyranny. By these practices and enticements the ancient dictators so successfully lulled their subjects under the yoke, that the stupefied peoples, fascinated by the pastimes and vain pleasures flashed before their eyes, learned subservience as naively, but not so creditably, as little children learn to read by looking at bright picture books.

Roman tyrants invented a further refinement. They often provided the city wards with feasts to cajole the rabble, always more readily tempted by the pleasure of eating than by anything else. The most intelligent and understanding amongst them would not have quit his soup bowl to recover the liberty of the Republic of Plato. Tyrants would distribute largess, a bushel of wheat, a gallon of wine, and a sesterce: and then everybody would shamelessly cry, "Long live the King!" The fools did not realize that they were merely recovering a portion of their own property, and that their ruler could not have given them what they were receiving without having first taken it from them.

Les theatres, les jeus, les farces, les spectacles, les gladiateurs, les bestes estranges, les medailles, les tableaus et autres telles drogueries c'estoient aus peuples anciens les apasts de la servitude, le pris de leur liberté, les outils de la tirannie: ce moien, ceste pratique, ces alleschemens avoient les anciens tirans pour endormir leurs subjects sous le joug. Ainsi les peuples assotis trouvans beaus ces passetemps amusés d'un vain plaisir qui leur passoit devant les yeulx, s'accoustumoient a servir aussi niaisement, mais plus mal que les petits enfans, qui pour voir les luisans images des livres enluminés aprenent a lire.

Les rommains tirans s'adviserent ancore d'un autre point de festoier souvent les dizaines publiques abusant ceste canaille comme il falloit, qui se laisse aller plus qu'a toute autre chose au plaisir de la bouche. Le plus avisé et entendu d'entr'eus n'eust pas quitté son esculée de soupe pour recouvrer la liberté de la republique de Platon. Les tirans faisoient largesse d'un quart de blé, d'un sestier de vin, et d'un sesterce; et lors c'estoit pitié d'ouir crier Vive le roi: les lourdaus ne s'avisoient pas qu'ils ne faisoient que recouvrer une partie du leur, et que cela mesmes qu'ils recouvroient, le tiran ne le leur eust peu donner, si devant il ne l'avoit osté à eus mesmes.

Another Bundle of Contradictions

Historia Augusta, 6: Life of Avidius Cassius 3.4 (tr. David Magie):

Such was his character, then, that sometimes he seemed stern and savage, sometimes mild and gentle, often devout and again scornful of sacred things, addicted to drink and also temperate, a lover of eating yet able to endure hunger, a devotee of Venus and a lover of chastity.See Thomas Wiedemann, "The Figure of Catiline in the Historia Augusta," Classical Quarterly 29.2 (1979) 479-484 (esp. 482-483), who remarks (at 480, footnotes omitted):

fuit his moribus, ut nonnumquam trux et asper videretur, aliquando mitis et lenis, saepe religiosus, alias contemptor sacrorum, avidus vini item abstinens, cibi adpetens et inediae patiens, Veneris cupidus et castitatis amator.

Men who were not straightforwardly black or white were rather a problem for educated Romans. Popular moral philosophy assumed that a man's character (physis, natura) never normally changed: the Lives of Plutarch are perhaps the most obvious expression of this widespread attitude. But this was not just a philosophical postulate. During their years at school, Romans had not merely read through with their grammaticus innumerable character-sketches in historians and orators which were little more than lists of either good or bad qualities; they had formally learnt at the rhetorician's school the framework into which any conceivable person would have to be fitted if he was going to be mentioned in a speech, either positively or negatively. We can see this (for example) from Cicero's summary of the 'laudandi vituperandique rationes' in the Partitiones Oratoriae, or Quintilian's scheme 'de laude ac vituperatione'.Related post: A Bundle of Contradictions.

After this kind of education, any figure who combined positive and negative qualities was bound to be a problem...

Saturday, October 14, 2017

The Great and the Good, Doing What No One Else Can Do for Them

Thanks to a friend (or enabler, as the case may be) for sending me this photograph of a shop display in Barcelona:

Caganers — they're not just for Christmas. The title of this post comes from Cervantes, Don Quixote 1.21 (lo que otro no pudiera hacer por el). Here is the entire passage, one of my favorites, in John Ormsby's translation:

Caganers — they're not just for Christmas. The title of this post comes from Cervantes, Don Quixote 1.21 (lo que otro no pudiera hacer por el). Here is the entire passage, one of my favorites, in John Ormsby's translation:

Just then, whether it was the cold of the morning that was now approaching, or that he had eaten something laxative at supper, or that it was only natural (as is most likely), Sancho felt a desire to do what no one could do for him; but so great was the fear that had penetrated his heart, he dared not separate himself from his master by as much as the black of his nail; to escape doing what he wanted was, however, also impossible; so what he did for peace's sake was to remove his right hand, which held the back of the saddle, and with it to untie gently and silently the running string which alone held up his breeches, so that on loosening it they at once fell down round his feet like fetters; he then raised his shirt as well as he could and bared his hind quarters, no slim ones. But, this accomplished, which he fancied was all he had to do to get out of this terrible strait and embarrassment, another still greater difficulty presented itself, for it seemed to him impossible to relieve himself without making some noise, and he ground his teeth and squeezed his shoulders together, holding his breath as much as he could; but in spite of his precautions he was unlucky enough after all to make a little noise, very different from that which was causing him so much fear.

Don Quixote, hearing it, said, "What noise is that, Sancho?"

"I don't know, senor," said he; "it must be something new, for adventures and misadventures never begin with a trifle." Once more he tried his luck, and succeeded so well, that without any further noise or disturbance he found himself relieved of the burden that had given him so much discomfort. But as Don Quixote's sense of smell was as acute as his hearing, and as Sancho was so closely linked with him that the fumes rose almost in a straight line, it could not be but that some should reach his nose, and as soon as they did he came to its relief by compressing it between his fingers, saying in a rather snuffing tone, "Sancho, it strikes me thou art in great fear."

"I am," answered Sancho; "but how does your worship perceive it now more than ever?"

"Because just now thou smellest stronger than ever, and not of ambergris," answered Don Quixote.

"Very likely," said Sancho, "but that's not my fault, but your worship's, for leading me about at unseasonable hours and at such unwonted paces."

"Then go back three or four, my friend," said Don Quixote, all the time with his fingers to his nose; "and for the future pay more attention to thy person and to what thou owest to mine; for it is my great familiarity with thee that has bred this contempt."

"I'll bet," replied Sancho, "that your worship thinks I have done something I ought not with my person."

"It makes it worse to stir it, friend Sancho," returned Don Quixote.

Labels: noctes scatologicae

Death-Bed Decorum

George Santayana (1863-1952), "Death-Bed Manners," Soliloquies in England and Later Soliloquies (London: Constable and Company Ltd., 1922), pp. 90-92 (at 91-92):

No summoning of priests, no great concourse of friends and relations, no loud grief, no passionate embraces and poignant farewells; no endless confabulations in the antechamber, no gossip about the symptoms, the remedies, or the doctors' quarrels and blunders; no breathless enumeration of distinguished visitors, letters, and telegrams; no tearful reconciliation of old family feuds nor whisperings about the division of the property.Related post: My Bed of Death.

Instead, either silence and closed doors, if there is real sorrow, or more commonly only a little physical weariness in the mourners, a little sigh or glance at one another, as if to say: We are simply waiting for events; the doctors and nurses are attending to everything, and no doubt, when the end comes, it will be for the best.

In the departing soul, too, probably dulness and indifference. No repentance, no anxiety, no definite hopes or desires either for this life or for the next. Perhaps old memories returning, old loves automatically reviving; possibly a vision, by anticipation, of some reunion in the other world: but how pale, how ghostly, how impotent this death-dream is!

I seem to overhear the last words, the last thoughts of a mother: "Dear children, you know I love you. Provision has been made. I should be of little use to you any longer. How pleasant to look out of that window into the park! Be sure they don't forget to give Pup some meat with his dog-biscuit." It is all very simple, very much repressed, the pattering echo of daily words.

Death, it is felt, is not important. What matters is the part we have played in the world, or may still play there by our influence. We are not going to a melodramatic Last Judgement. We are shrinking into ourselves, into the seed we came from, into a long winter's sleep. Perhaps in another springtime we may revive and come again to the light somewhere, among those sweet flowers, those dear ones we have lost. That is God's secret. We have tried to do right here. If there is any Beyond, we shall try to do right there also.

IQ Contest

Toluse Olorunnipa, "Trump Suggests He'd Beat Tillerson in an IQ Test," Bloomberg (October 10, 2017):

President Donald Trump defended his intelligence after reports that Secretary of State Rex Tillerson called him a "moron."Historia Augusta, 1: Life of Hadrian 15.10-13 (tr. David Magie):

"I think it's fake news, but if he did that, I guess we'll have to compare IQ tests," Trump said in an interview with Forbes Magazine published Tuesday. "And I can tell you who is going to win."

[10] And although he was very deft at prose and at verse and very accomplished in all the arts, yet he used to subject the teachers of these arts, as though more learned than they, to ridicule, scorn, and humiliation. [11] With these very professors and philosophers he often debated by means of pamphlets or poems issued by both sides in turn. [12] And once Favorinus, when he had yielded to Hadrian's criticism of a word which he had used, raised a merry laugh among his friends. For when they reproached him for having done wrong in yielding to Hadrian in the matter of a word used by reputable authors, [13] he replied: "You are urging a wrong course, my friends, when you do not suffer me to regard as the most learned of men the one who has thirty legions".

[10] et quamvis esset oratione et versu promptissimus et in omnibus artibus peritissimus, tamen professores omnium artium semper ut doctior risit contempsit obtrivit. [11] cum his ipsis professoribus et philosophis libris vel carminibus invicem editis saepe certavit. [12] et Favorinus quidem, cum verbum eius quondam ab Hadriano reprehensum esset, atque ille cessisset, arguentibus amicis, quod male cederet Hadriano de verbo quod idonei auctores usurpassent, risum iucundissimum movit. [13] ait enim: 'non recte suadetis, familiares, qui non patimini me illum doctiorem omnibus credere, qui habet triginta legiones.'

Friday, October 13, 2017

Withdraw Your Support

Étienne de La Boétie (1530-1563), Discourse on Voluntary Servitude (tr. Harry Kurz):

Resolve to serve no more, and you are at once freed. I do not ask that you place hands upon the tyrant to topple him over, but simply that you support him no longer; then you will behold him, like a great Colossus whose pedestal has been pulled away, fall of his own weight and break into pieces.

Soiés resolus de ne servir plus, et vous voila libres; je ne veux pas que vous le poussies ou l'esbranlies, mais seulement ne le soustenés plus, et vous le verrés comme un grand colosse a qui on a desrobé la base, de son pois mesme fondre en bas et se rompre.

Haste

Procopius, Buildings 2.1.8 (tr. H.B. Dewing):

For stability is never likely to keep company with speed, nor is accuracy wont to follow swiftness.Plutarch, Life of Pericles 13.2 (tr. Bernadotte Perrin):

τῷ γὰρ συντόμῳ τό γε ἀσφαλὲς οὐδαμῆ εἴωθε ξυνοικίζεσθαι, οὐδὲ τῷ ὀξεῖ τὸ ἀκριβὲς φιλεῖ ἕπεσθαι.

And yet they say that once on a time when Agatharchus the painter was boasting loudly of the speed and ease with which he made his figures, Zeuxis heard him, and said, "Mine take, and last, a long time." And it is true that deftness and speed in working do not impart to the work an abiding weight of influence nor an exactness of beauty; whereas the time which is put out to loan in laboriously creating, pays a large and generous interest in the preservation of the creation.

καίτοι ποτέ φασιν Ἀγαθάρχου τοῦ ζωγράφου μέγα φρονοῦντος ἐπὶ τῷ ταχὺ καὶ ῥᾳδίως τὰ ζῷα ποιεῖν ἀκούσαντα τὸν Ζεῦξιν εἰπεῖν· "Ἐγὼ δ᾿ ἐν πολλῷ χρόνῳ." ἡ γὰρ ἐν τῷ ποιεῖν εὐχέρεια καὶ ταχύτης οὐκ ἐντίθησι βάρος ἔργῳ μόνιμον οὐδὲ κάλλους ἀκρίβειαν· ὁ δ᾿ εἰς τὴν γένεσιν τῷ πόνῳ προδανεισθεὶς χρόνος ἐν τῇ σωτηρίᾳ τοῦ γενομένου τὴν ἰσχὺν ἀποδίδωσιν.

The Scum of the Earth

George Santayana (1863-1952), "The Irony of Liberalism," Soliloquies in England and Later Soliloquies (London: Constable and Company Ltd., 1922), pp. 178-189 (at 189):

The scum of the earth gathers itself together, becomes a criminal or a revolutionary society, finds some visionary or some cosmopolitan agitator to lead it, establishes its own code of ethics, imposes the desperate discipline of outlaws upon its members, and prepares to rend the free society that allowed it to exist.

Thursday, October 12, 2017

Last Wishes

Euripides, Orestes 1163-1166 (tr. David Kovacs):

Now since I am in any case going to breathe out my life,

I want to do something to my enemies before I die

so that I can repay with destruction those who have betrayed me 1165

and so that those who have made me miserable may smart for it.

ἐγὼ δὲ πάντως ἐκπνέων ψυχὴν ἐμὴν

δράσας τι χρῄζω τοὺς ἐμοὺς ἐχθροὺς θανεῖν,

ἵν᾿ ἀνταναλώσω μὲν οἵ με προύδοσαν, 1165

στένωσι δ᾿ οἵπερ κἄμ᾿ ἔθηκαν ἄθλιον.

The Surest Proof of Stupidity

Montaigne (1533-1592), Essais 8.3 (tr. Donald M. Frame):

Obstinacy and heat of opinion is the surest proof of stupidity. Is there anything so certain, resolute, disdainful, contemplative, grave, and serious as an ass?

L'obstination et ardeur d'opinion, est la plus seure preuve de bestise. Est il rien certain, resolu, dedeigneux, contemplatif, serieux, grave, comme l'asne?

The Ancient, Fundamental, Normal State of the World

George Santayana (1863-1952), "Tipperary," Soliloquies in England and Later Soliloquies (London: Constable and Company Ltd., 1922), pp. 99-106 (at 101):

If experience could teach mankind anything, how different our morals and our politics would be, how clear, how tolerant, how steady! If we knew ourselves, our conduct at all times would be absolutely decided and consistent; and a pervasive sense of vanity and humour would disinfect all our passions, if we knew the world. As it is, we live experimentally, moodily, in the dark; each generation breaks its egg-shell with the same haste and assurance as the last, pecks at the same indigestible pebbles, dreams the same dreams, or others just as absurd, and if it hears anything of what former men have learned by experience, it corrects their maxims by its first impressions, and rushes down any untrodden path which it finds alluring, to die in its own way, or become wise too late and to no purpose.Id. (at 103-104):

Reserve a part of your wrath; you have not seen the worst yet. You suppose that this war has been a criminal blunder and an exceptional horror; you imagine that before long reason will prevail, and all these inferior people that govern the world will be swept aside, and your own party will reform everything and remain always in office. You are mistaken. This war has given you your first glimpse of the ancient, fundamental, normal state of the world, your first taste of reality. It should teach you to dismiss all your philosophies of progress or of a governing reason as the babble of dreamers who walk through one world mentally beholding another.

Compromise

George Santayana (1863-1952), "The English Church," Soliloquies in England and Later Soliloquies (London: Constable and Company Ltd., 1922), pp. 83-88 (at 83):

Compromise is odious to passionate natures because it seems a surrender, and to intellectual natures because it seems a confusion; but to the inner man, to the profound Psyche within us, whose life is warm, nebulous, and plastic, compromise seems the path of profit and justice. Health has many conditions; life is a resultant of many forces. Are there not several impulses in us at every moment? Are there not several sides to every question? Has not every party caught sight of something veritably right and good? Is not the greatest practicable harmony, or the least dissension, the highest good?Id. (at 85):

Heresy is to be conceived as eccentricity within the fold, not as separation from it; it is the tacking of the ship on its voyage.

Wednesday, October 11, 2017

A Bundle of Contradictions

Historia Augusta, 1: Life of Hadrian 14.11 (tr. David Magie):

He was, in the same person, austere and genial, dignified and playful, dilatory and quick to act, niggardly and generous, deceitful and straightforward, cruel and merciful, and always in all things changeable.One can imagine other supplements, e.g. apertus (or perhaps even apertior, accounting for the omission by homoeoteleuton). I don't have access to Herbert W. Benario, A Commentary on the Vita Hadriani in the Historia Augusta (Chico: Scholars Press, 1980), Barry Baldwin, "Hadrian's Character Traits," Gymnasium 101 (1994) 455-456, or Jörg Fündling, Kommentar zur Vita Hadriani der Historia Augusta (Bonn: Habelt, 2006). The critical apparatus in Ernest Hohl's Teubner edition (1965) is very spare.

idem severus comis, gravis lascivus, cunctator festinans, tenax liberalis, simulator <simplex>, saevus clemens, et semper in omnibus varius.

simplex add. Reimarus (dissimulator Hohl, sincerus Brakmann)

Border Control

Historia Augusta, 1: Life of Hadrian 12.6 (tr. David Magie):

During this period and on many other occasions also, in many regions where the barbarians are held back not by rivers but by artificial barriers, Hadrian shut them off by means of high stakes planted deep in the ground and fastened together in the manner of a palisade.Id. 11.2:

per ea tempora et alias frequenter in plurimis locis, in quibus barbari non fluminibus sed limitibus dividuntur, stipitibus magnis in modum muralis saepis funditus iactis atque conexis barbaros separavit.

And so, having reformed the army quite in the manner of a monarch, he set out for Britain, and there he corrected many abuses and was the first to construct a wall, eighty miles in length, which was to separate the barbarians from the Romans.

ergo conversis regio more militibus Britanniam petiit, in qua multa correxit murumque per octoginta milia passuum primus duxit, qui barbaros Romanosque divideret.

regio codd.: egregio Novák: rigido Frankfurter: recto Baehrens

The Path to Contentment

Diogenes of Oenoanda, fragment 40, tr. C.W. Chilton in Diogenes of Oenoanda, The Fragments. A Translation and Commentary (London: Oxford University Press, 1971), p. 18:

Thanks very much to the friend who gave me a copy of Chilton's translation of Diogenes of Oenoanda. For me, books like this are "productive of contentment."

Nothing is so productive of contentment as not being too busy, not undertaking disagreeable tasks, and not pushing ourselves beyond our powers; for all these things cause worry and trouble to our nature.Greek text, from Diogenis Oenoandensis Fragmenta, ed. C.W. Chilton (Leipzig: B.G. Teubner, 1967), p. 71:

Οὐδὲν οὕτως εὐθυµίας ποιητικὸν ὡς τὸ µὴ πολλὰ πράσσειν µηδὲ δυσκόλοις ἐπιχειρεῖν πράγμασιν µηδὲ παρὰ δύναμίν [τ]ι βιάζεσθαι τὴν ἑαυτοῦ· πάντα γὰρ ταῦτα ταραχὰς ἐνποιεῖ τῆ φύσ[ει.]I was surprised to see τῆ without an iota subscript, but it's also printed that way in Ernst Kalinka and Rudolf Heberdey, "L'inscription philosophique d'Oenoanda," Bulletin de correspondance hellénique 21 (1897) 345-443 (at 374; fragment 27), and in Diogenis Oenoandensis Fragmenta, ed. Iohannes William (Leipzig: B.G. Teubner, 1907), p. 54 (fragment LVI). The iota subscript seems to be present in Epicuro, Opere. Introduzione, testo critico, traduzione e note di Graziano Arrighetti (Turin: Giulio Einaudi Editore, 1960), p. 508, unless my eyes are playing tricks on me.

Thanks very much to the friend who gave me a copy of Chilton's translation of Diogenes of Oenoanda. For me, books like this are "productive of contentment."

Tuesday, October 10, 2017

An Odd Duck

Lee Child, 61 Hours (New York: Delacorte Press, 2010), p. 81:

"Lowell's an odd duck," Peterson said. "He's a loner. He reads books."Hat tip: A friend.

Regress, not Progress

H.D. Jocelyn, "The Teubner of Varro's Menippean Satires,"

Classical Review 38.1 (1988) 33-36 (at 36):

These things were much better done in the nineteenth century.

Flocking Together

Cicero, On Old Age 3.7 (tr. Cyrus R. Edmonds):

Equals with equals, according to the old proverb, most easily flock together.A. Otto, Die Sprichwörter und sprichwörtlichen Redensarten der Römer (Leipzig: B.G. Teubner, 1890), p. 264:

pares autem vetere proverbio cum paribus facillime congregantur.